-

Url copied to clipboard.

Collectively written by the RiskLogic team.

Nine-eleven are two of the most infamous numbers in history. They represent unimaginable disaster and loss and remain a pivotal moment in the journey to corporate resilience.

The digital atmosphere shows evidence of taking a break from an onslaught of covid-19 updates while stories, videos, and tributes of a looming anniversary arrive.

“Having seen the impacts of terrorism firsthand during my time in Northern Ireland and Bosnia through the British Army, you can get to a point of assuming there must be a limit to how far these people will go.

“Twelve years later, sitting at my desk, supporting a tie in place of military stripes, I watched the unfolding event in New York. Anger crept in, not just because of the attack, but that with all these precautions, all these measures we can take, we’re never exempt from a crisis event; these people still got through.

“It reminds me every day of the importance of resilience and preparedness. It is, unquestionably, what saved the thousands of people who did make it out of 9/11 alive”.

Invest in any one of our resilience programs in Adelaide, Australia and you will get a unique experience with RiskLogic’s Principal Consultant.

Their professional journey is vast and relevant to that of 9/11. Her time at the New South Wales Police Forensic Counter Terrorism agency saw her involved in the aftermaths of mass fatalities, the Bali bombings, the Indian Ocean Tsunami, and the Anthrax Attacks. She later joined INTERPOL serving three years as an Executive within the Counter Terrorism and Emerging Threats Directorate.

“That day (9/11) was a turning point on my life’s path. Not only in terms of my own career, catapulting me out of Public Health and into a future related to Counter Terrorism preparedness and response, but also personally.

“The subsequent response and investigation that unfolded over the next two decades enabled me to work with a variety of national and international agencies, organisations and individuals. The experience of those interactions and exposure to inner workings of multi-organisational, cross jurisdictional teams, has provided invaluable learnings that I have utilised, shared and endeavored to continually grow from”.

One man’s resilience that shaped business continuity

Rick Rescorla suspected a major attack on the Twin Towers eight years before the event. The documentation that today provides evidence of his concerns has become the cornerstone of many evacuation plans, drills and procedures leading up to 2001.

Morgan Stanley executive Bill McMahon stated that Rescorla not only saved over 2,500 employees that day, but he also saved 250 visiting guests for a stockbroker training class. “They knew where to go, Rick showed them the staircase and the evacuation points”.

Often missed from Rescorla’s inspiring story are the reasons to why this man was so passionate about resiliency.

On February 26th, 1993, six terrorists set off a 606 kg urea nitrate–hydrogen gas enhanced device with the intention to topple the North Tower into the South, bringing both buildings down and killing thousands.

The attack failed to complete its overall objective but killed six people; it was enough to convince Rescorla to act. He found the evacuation of fifty thousand people that day to have been poorly handled and vowed that “such a muddled exodus” would never happen again.

The seven years following, Rescorla’s resilience journey landed him as the Director of Security for Dean Witter/Morgan Stanley in 1997. Convinced of the evolution of terrorism, he began writing what is now known as the The Morgan Stanley Employee’s Bible.

This document became a cult sensation, an instantly recognizable document, the subject of numerous nicknames and euphemisms. It details clear procedures and schedules to practice disruptive events. You could not find a coffee table in the Morgan Stanley Trade Centre offices without it.

In 1999, Rescorla and his team were publicly acknowledged for their efforts in Emergency Management and Security. He molded the people around him to live and breathe situational awareness. These people trusted him, and it spread into other organisations throughout the Trade Centre too. Soon, he was seen visiting businesses weekly to check on their response training and capabilities.

Despite all this preparedness, Rescorla could not shake that another attack was possible. On the morning of September, the 11th, as the Port Authority ordered everyone to remain in place, from the 38th floor of Tower 2, Rescorla watched the first plane fly into the adjacent building. He could not quite believe his eyes; what he had spent seven years preparing thousands of people for was happening.

Choosing to ignore instructions through the building’s PA system, he reminded his team of the plans and procedures they had trained against so heavily. He saved nearly three thousand people that day. Running back into Tower 1, he was never seen again.

When putting the call out to obtain experiences and stories for this article, nearly 20 consultants named Rick Rescorla’s story as pivotal to 9/11. He is arguably the most referenced case study in business continuity.

Deutsche Bank vs Merrill Lynch and Lehman Brothers

No organisation wants to be singled out in such a significant story in human history, but if you are, you want it to be one of positive action.

Following the collapse of Tower 1, Deutsche Bank Tower at 130 Liberty Street, New York became uninhabitable. As planned and practiced, all the Deutsche Bank staff were safely relocated to their business continuity site at lower Manhattan.

Concise and tested plans at the organisation meant that the group could avoid serious human and customer impacts, loss of income, unplanned expenses, loss of critical information, and failures to meet on-going commitments to stakeholders. They remained operational and active. Many staff present on that day are still with the business today.

“It was amazing how quickly the U.S. operation moved over to New Jersey”, recalls RiskLogic’s National Administration Assistant Gareth Perkins.

“I was working for American Express at the time. It was extremely busy as we were dealing with a lot of overflow U.S. calls due to time difference and language. I recall mattresses in the office to allow some people to nap between phone calls.

“The business [American Express] was also amazingly flexible with getting customer emergency cards, with some staff members even delivering new cards via taxi to their customers!”

For Merrill Lynch, the outcome was different. Loss of entire production and development centres were instant and long lasting. There was no control over capacity and the corporate functions within their site. The result, ten thousand lost jobs and $43 million in lost revenue.

Lehman Brothers employees squeezed into Jersey City where they bought a second building to operate from in the following months of 9/11. In Manhattan, they rented office space and hired the Sheraton Hotel, other employees worked from home, but none of these steps were planned. In a time when the idea of Zoom was alien, a dispersed workforce became impossible to manage and ultimately cost the business $3 million in lost revenue.

Pushed on by global government policy updates, the trajectory of terrorism defense changed the landscape many businesses operated in post 2001. Business-as-usual took some American organisations years to return to because of disruptive (and some might argue abused) surveillance and policy changes by the U.S. government.

A time before virtual conferences and webinars, restrictions on travel had businesses falling behind a fast paced Asian and European market.

It is unclear how long it took businesses to return to an operational status in New York City. But what is clear are the ones that had a near immediate return, were the ones that planned for such a disruption.

The economic impact of 9/11

As we’re seeing with the current global pandemic, even the smallest ripple of change – whether positive or negative – can create a tsunami of disruption. 9/11 is such an extreme example, that many wouldn’t dare compare it to the slow burning nature of a pandemic. However, the aftereffects from an economic standpoint show similarities worth learning from.

“For nineteen years, 9/11 was the standout event that no one expected or could believe happened. Now it’s covid. It’s a similar story; many refusing to believe the impacts of a pandemic like this. Until 2020, a pandemic scenario exercise of this scale would have been considered ‘unrealistic’. So too was the concept of what happened to the Twin Towers up until 2001”, says Principal Consultant Mark Watson.

“I was in Sydney working on scenarios with my colleague in the US for the upcoming Salt Lake Winter Olympics Games-wide Readiness Exercise. I was preparing for bed when he messaged me with “wow, a plane crashed into the World Trade Centre and the tower is on fire”. What a farfetched idea for an exercise scenario I thought. The next morning when I woke, it all became reality and very real”.

The attacks had an immediate negative effect on the U.S. economy, in particular New York City. Wall Street and the NY Stock Exchange saw an immediate drop as the market fell 7.1%, or 684 points. The city’s economy saw a loss of 143,000 jobs in one month and $2.8 billion in wages in the first three months. The GDP of New York City was estimated to have declined by $30.3 billion over the last three months of 2001 and all of 2002.

Approximately 18,000 small businesses were destroyed or displaced after the attacks. The Small Business Administration provided loans as assistance in conjunction with Community Development Block Grants and Economic Injury Disaster Loans provided by the Federal Government.

Also similar to our current covid-19 pandemic, one of the biggest losses was in the air transportation industry which accounted for 60% of lost jobs overall.

What was the cost of 9/11 to the rest of the country?

According to a survey by The New York Times, 3.3 trillion dollars. That’s about $7 million to every dollar Al Qaeda spent on planning and executing the attack. The cost to clean the debris and begin opening the city back to the world was reported at $750 million.

On a global scale, the argument can be made that other countries saw little to no impact directly out of New York. But twenty years of study suggests that the swift changes in policy and sharp shifts in health, security and border control out of the US (one of the world’s leading suppliers and markets) has heavily stunted productivity and growth to some key trading partners.

Canada, Mexico, and Japan saw huge shifts in their ability to meet and adjust to changing rules, customer demand and regulations. Canada saw impacts with exported goods to the States. Measures were put in place to minimize the disruptions, however, motor vehicles – a major supply to America – saw about a 40% impact in output.

There is evidence to suggest that the onset of the security regulations and change in trade strategies with the U.S. unintentionally contributed to the world economy remaining efficient and functioning in follow up disasters and events. However, this is intangible and immeasurable.

But then there is the cost of war.

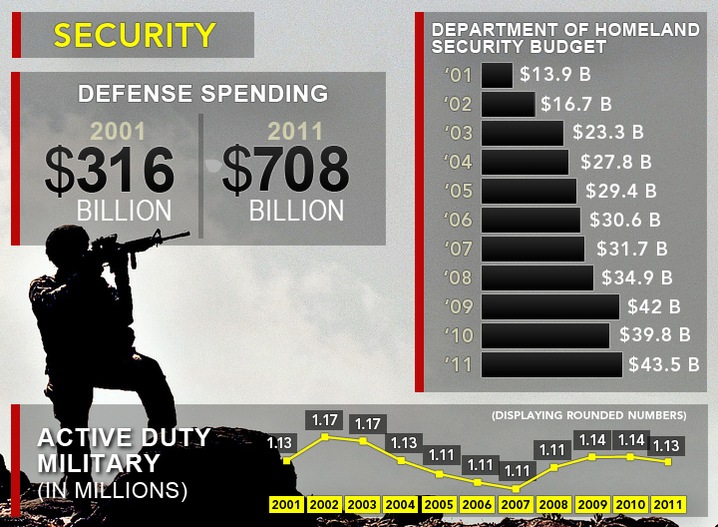

Military spending doubled to $700 billion in the decade following 9/11, to about 20% of total government spending. In 2001, the Defense Department had about $181 billion in contract obligations to 46,000 companies. In 2011, it had $375 billion in obligations to 110,000+ contractors. Increased military spending by the government turned the Washington, DC, area into the country’s hottest regional economy from 2001–2011.

When President George W. Bush ordered a “war on terror”, America would lose approximatelytwo and a half thousand service men and women throughout the next twenty years.

Therefore, many can be forgiven for feeling hollow off the back of that bleak time throughout Afghanistan and its neighboring countries. After the final few U.S. Troops left the middle east, seconds prior to the Taliban gaining full control of the country, the States had reportedly injected $5.8 trillion dollars into the war effort (including interest on debt and financing).

For counter-terrorism, Co-Director of The Costs of War project at Brown University’s Watson Institute, Neta Crawford says that the United States budgetary costs and obligations of post-9/11 wars throughout the 2020 financial year were actually $6.4 trillion.

Whatever the final figure, this financial commitment and decision to continue a twenty year war has crippled the American economy multiple times over. It begs to question, does “war” need to be a disruption practiced in our plans?

The answer is yes.

Communication Channels with U.S. & UK

I later found out that 658 staff, the entire workforce who showed up that day, had died.

The Twin Towers were a hub of multinational entities and professionals of all expertise. With 110 stories each, the two towers made up nearly ten million square feet of office space. 350 businesses and 35,000 employees occupied the buildings. For the United Kingdom, it was hard to find an international business in London who didn’t have direct lines to someone in one of those towers.

David Gumley, Head of Growth at RiskLogic, recalls the event vividly as he sat stunned at the mirrored TV screens in his London office.

“I was just heading back to my desk on the Barclays Capital trading floor, having just popped out to grab a late-lunch. I remember one of the FX dealers saying that he couldn’t connect with our U.S. desk for the morning briefings, as there seemed to be a problem with their phone lines.

“There was a bit of commotion starting to filter around the floor as several of our teams couldn’t connect with U.S. counterparts and market makers to fill early U.S. trade orders. It was then that I got a call from a friend of mine.

“He described that he and his UK colleagues couldn’t contact any of their US team. The news feeds into the floor we occupied started to switch and the pictures of the event unfolding started to filter through. I remember sitting for what seemed like hours just looking at the TV screens with the surrounding phones creating a wall of deafening noise.

“We were all told to make our way home in fear that other financial centres may be on the ‘attack list’. I called my friend later that evening and he told me that all his U.S. colleagues had likely died as their floors were between 101-105 of 1WTC, which by this time we knew had completely collapsed. I later found out that 658 staff, the entire workforce who showed up that day, had died”.

David agrees that this sort of experience and the sheer number of losses changed corporate resilience forever. “I believe that the 9/11 experience was the impetus for major changes. The event shaped corporate resilience, as to what we know today.

“Disaster Recovery strategies were executed globally almost simultaneously, back-up facilities were identified, and staff began relocating to these. Technicians worked through the night to get workstations and communication channels up and running again. The bandwidth between U.S. & UK operations was increased to support such events in the future”.

Plan, do, check and act

No matter how far we research, our consulting team is always brought back to the unique individuals who learnt and acted upon the event; a pivot in risk management as we know it.

These case studies, like that of Rick Rescorla, are ones there to inspire the next generation of resilience experts, leaders, and professionals. This unique anniversary should be a time to pause and check on your people, to ask yourself that as part of your responsibility, do you have a plan? Do you train it out? Validate it? Practice it? Do you regularly check for gaps? If you found any, how did you act upon them?

2,977 people lost their lives 20 years ago this week. But tens of thousands were saved due to the processes and resilience of those around us.There are thousands of case studies from people, organisations and emergency services of that day, each as humbling as the next. But, as devastating of an event that it was, we must seek to study and learn from the impacts. To increase organisational and personal resilience, we must focus on what went right, and what went wrong. Otherwise, this loss was for nothing.